Female's Preferred Birth Interval in Uganda: What Are The Associated Factors?

Abstract

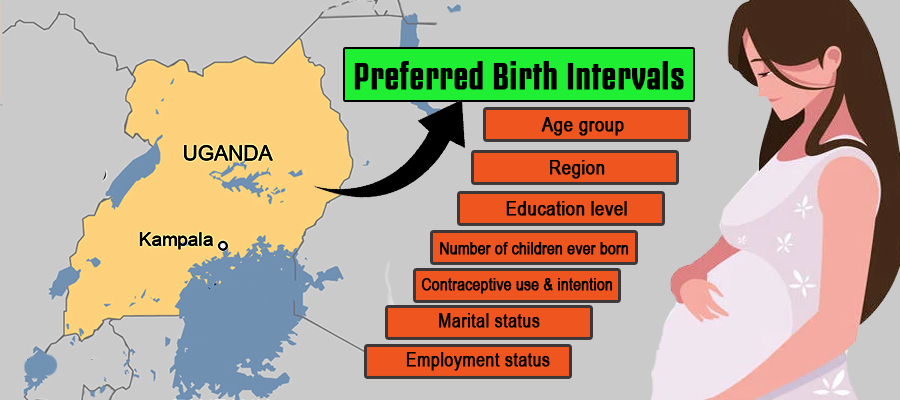

Preferred birth intervals of females can have potential effects on several maternal and neonatal health outcomes. Therefore, this study aims to ascertain factors associated with preferred birth intervals among females in Uganda. The data utilized were obtained from the 2016 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey. The Pearson chi-square test and logistic regression model were used to identify independent variables significantly associated with preferred birth intervals. The results showed that the majority of females or 77.1% preferred birth intervals of at least two years. The independent factors that significantly influenced their preferences included age group, region, education level, children ever born, contraceptive use and intention, marital status, as well as current employment status. Therefore, interventions aimed at educating females about birth intervals should be tailored to the specific regions, considering their education and level of exposure to contraceptives. This knowledge will enable females to understand the information provided, which is key to making healthy choices consistent with WHO recommendations.

Downloads

References

Afolabi, R. F., & Palamuleni, M. E. (2022). Influence of Maternal Education on Second Childbirth Interval Among Women in South Africa : Rural-Urban Differential Using Survival Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221079920

Ajayi, A. I., & Somefun, O. D. (2020). Patterns and determinants of short and long birth intervals among women in selected sub-Saharan African countries. Medicine, 99(19), e20118. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000020118

Albin, O., Rademacher, N., Malani, P., Wafula, L., & Dalton, V. K. (2013). Attitudes toward birth spacing among women in Eastern Uganda. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 120(2), 194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.09.007

Aleni, M., Mbalinda, S. N., & Muhindo, R. (2020). Birth Intervals and Associated Factors among Women Attending Young Child Clinic in Yumbe Hospital, Uganda. International Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 2020, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1326596

Alhassan, A. R., Anyinzaam-Adolipore, J. N., & Abdulai, K. (2022). Short birth interval in Ghana: Maternal socioeconomic predictors and child survival. Population Medicine, 4(January), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.18332/POPMED/145914

Bauserman, M., Nowak, K., Nolen, T. L., Patterson, J., Lokangaka, A., Tshefu, A., Patel, A. B., Hibberd, P. L., Garces, A. L., Figueroa, L., Krebs, N. F., Esamai, F., Liechty, E. A., Carlo, W. A., Chomba, E., Mwenechanya, M., Goudar, S. S., Ramadurg, U., Derman, R. J., … Bose, C. (2020). The relationship between birth intervals and adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in six low and lower-middle income countries. Reproductive Health, 17(Suppl 2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-01008-4

Belaid, L., Atim, P., Ochola, E., Omara, B., Atim, E., Ogwang, M., Bayo, P., Oola, J., Okello, I. W., Sarmiento, I., Rojas-Rozo, L., Zinszer, K., Zarowsky, C., & Andersson, N. (2021). Community views on short birth interval in Northern Uganda: a participatory grounded theory. Reproductive Health, 18(88). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01144-5

Damtie, Y., Kefale, B., Yalew, M., Arefaynie, M., & Adane, B. (2021). Short birth spacing and its association with maternal educational status, contraceptive use, and duration of breastfeeding in Ethiopia. A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 16(2), e0246348. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246348

de Jonge, H. C. C., Azad, K., Seward, N., Kuddus, A., Shaha, S., Beard, J., Costello, A., Houweling, T. A. J., & Fottrell, E. (2014). Determinants and consequences of short birth interval in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(427). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-014-0427-6

Exavery, A., Mrema, S., Shamte, A., Bietsch, K., Mosha, D., Mbaruku, G., & Masanja, H. (2012). Levels and correlates of non-adherence to WHO recommended inter-birth intervals in Rufiji, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12(152). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-12-152

Garenne, M. (2004). Age at marriage and modernisation in sub-Saharan Africa. Southern African Journal of Demography, 9(2), 59–79. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20853271

Grundy, E., & Kravdal, Ø. (2014). Do short birth intervals have long-term implications for parental health? Results from analyses of complete cohort Norwegian register data. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68(10), 958–964. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204191

Hertrich, V. (2017). Trends in Age at Marriage and the Onset of Fertility Transition in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review, 43, 112–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12043

Islam, M. Z., Islam, M. M., Rahman, M. M., & Khan, M. N. (2022). Prevalence and risk factors of short birth interval in Bangladesh: Evidence from the linked data of population and health facility survey. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(4), e0000288. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000288

KNBS & ICF International. (2015). Kenya. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR308/FR308.pdf

Marston, M., Slaymaker, E., Cremin, I., Floyd, S., McGrath, N., Kasamba, I., Lutalo, T., Nyirenda, M., Ndyanabo, A., Mupambireyi, Z., & Zaba, B. (2009). Trends in marriage and time spent single in sub-Saharan Africa: A comparative analysis of six population-based cohort studies and nine Demographic and Health Surveys. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 85(SUPPL. 1). https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2008.034249

MoHCDGEC, MoH, NBS, OCGS, & ICF. (2016). Tanzania Demorgraphic and Health Survey Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS) 2015-2016. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr321/fr321.pdf

Olatoregun, O., Fagbamigbe Francis, A., Akinyemi Joshua, O., Oyindamola Bidemi, Y., & Bamgboye Afolabi, E. (2014). A Comparative Analysis of Fertility Differentials in Ghana and Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health, 18(3), 36–47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24362062.

Pimentel, J., Ansari, U., Omer, K., Gidado, Y., Baba, M. C., Andersson, N., & Cockcroft, A. (2020). Factors associated with short birth interval in low- And middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(156). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2852-z

Rasheed, P., & Al-Dabal, B. K. (2007). Birth interval: Perceptions and practices among urban-based Saudi Arabian women. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 13(4), 881–892. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17955772

Saadati, M., & Bagheri, A. (2019). Factors Affecting Preferred Birth Interval in Iran : Parametric Survival Analysis. 4, 40–48.

Singh, H., Sahoo, H., & Marbaniang, S. P. (2020). Birth interval and childhood undernutrition : Evidence from a large scale survey in India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 8(4), 1189–1194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2020.04.012

UBOS, & ICF. (2018). Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR333/FR333.pdf

WHO. (2005). Report of a WHO technical consultation on birth spacing. In Report of a WHO Technical Consultation on Birth Spacing (Vol. 13, Issue 6). http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/birth_spacing.pdf

Copyright (c) 2023 Douglas Candia, Edward Musoke, Christabellah Namugenyi

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial publication in this journal.

Authors are permitted to publish their work online in third parties as it can lead to wider dissemination of the work.